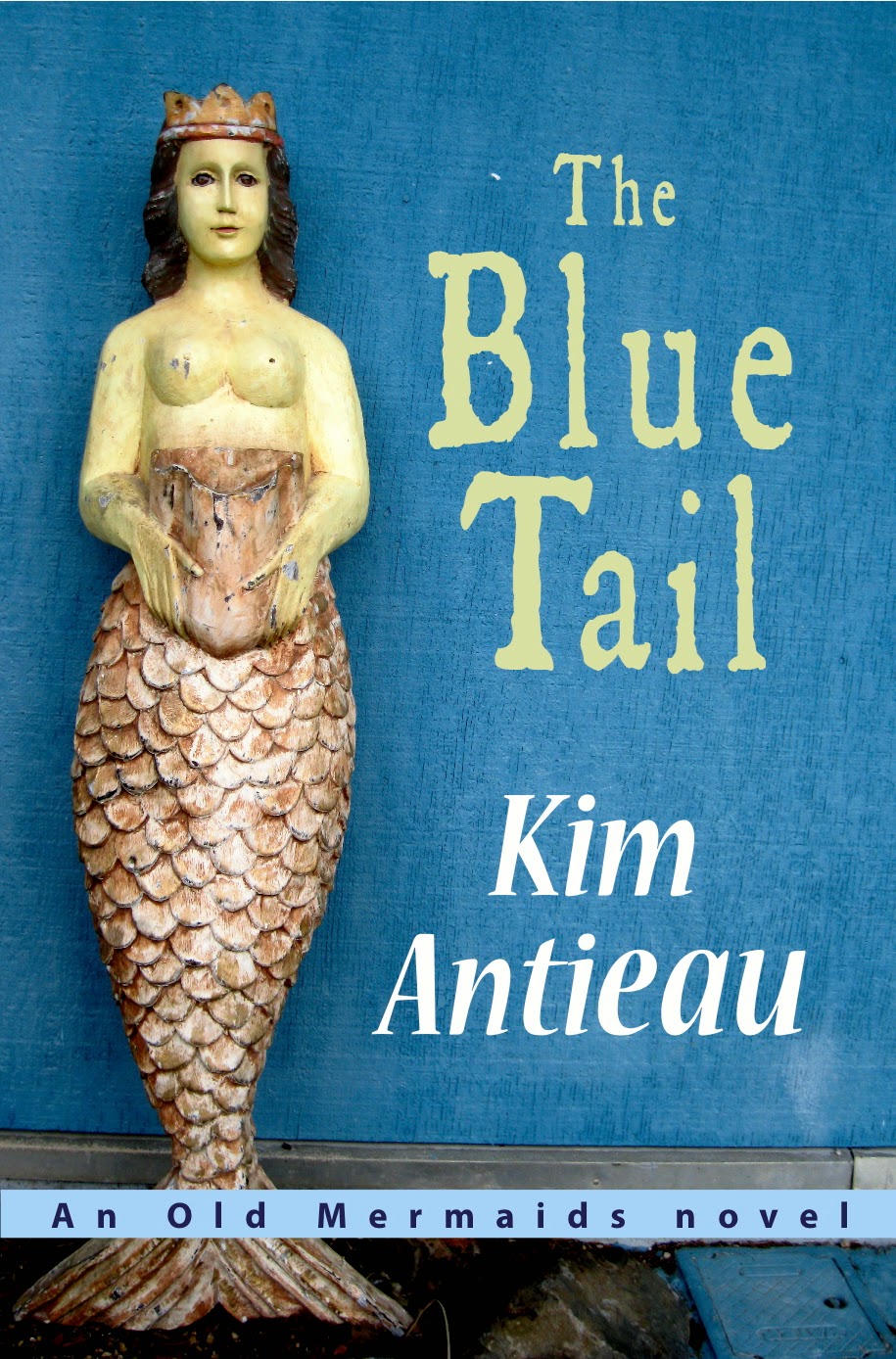

Chapter Four

Things change. Get over it.

—Sister Bea Wilder Mermaid

David and Maria did the dishes. Myla started to remind David that the house had a dishwasher, but she watched the two of them trying to talk to one another, and she decided to leave them alone. Theresa and Cathy sat in the living room and discussed job possibilities. Luisa and Stefan played cards at the kitchen table. Lily watched.

“What are you playing?” Myla asked.

“Old Maid,” Luisa said. She smiled as though she had said something very clever. “You wanna play?”

“Yeah, it’s kind of boring with just two players,” Stefan said.

Myla sat at the table with them. “How do you play this game?”

“First you take away one of the queens,” Luisa said. “Then you pass out all the cards to the players. Every player puts down all the pairs they have. Then you go around the circle and each player takes a card from the player on the right. If you get a pair with that card you put it down. You do this until one person is left with the single queen. The Old Maid. That person loses because she’s the Old Maid—she’s a loser because she’s all alone.”

Myla made a face. “The person who ends up with the Queen is the loser? She should be the winner!”

“It’s not the queen then,” Luisa said. “It’s the Old Maid. Get it. Everyone is in pairs except the queen. I mean, except the Old Maid.”

“Maybe she is like the queen bee,” Myla said. “The queen bee is not part of a pair. Or maybe she’s an old maid goddess, or an Old Mermaid goddess. Atargatis was a mermaid goddess, you know. Yemaya too. There are many others. Sometimes they were alone, sometimes they were part of a pair. That makes me think of something. Where’s the box the cards came in?”

Stefan handed it to her. She opened it and pulled out the joker.

“Let’s play Old Mermaids instead,” Myla said.

“Oh here we go!” Theresa said from the couch. She and Cathy got up and came over to the table.

“We need thirteen mermaids,” Myla said.

“Why?” Stefan asked.

“It’s a nice round number,” Myla answered.

Luisa frowned. Theresa laughed.

Myla began pulling the face cards out of the deck. When she had them all, she spread them out on the table and added the joker. “Here are the Old Mermaids! It’s played like Old Maid except whoever ends up with the most Old Mermaids wins. And the thirteenth Old Mermaid, if you get her, you get an additional thirteen points.”

“Is she making this up?” Luisa asked.

“I’m remembering it as I talk about it,” Myla said.

“She does that a lot,” Theresa said.

“Shall we play?” Myla asked.

“These look like mermen, not mermaids,” Luisa said.

“Where do you think little mermaids come from?” Stefan asked.

Myla laughed. “Well, that is a story for another night too.” She picked up one of the cards. “We could decorate these and make them all into Old Mermaids.”

“You mean draw on them?” Stefan asked.

“Why not?” Myla looked up at David who had come over to watch. “They’re your cards, I presume?”

“Do whatever you like with them,” David said.

“I’ve got crayons, pencils, and markers at my place,” Myla said. “David, you’re an artist. What about your room here? Do you still have anything here?”

“There might be something in the closet,” he said. “I’ll go look.”

“I’ll come with,” Luisa said.

“Me, too,” Stefan said. Luisa gave him a dirty look. Lily slipped her hand into Luisa’s.

“We’ll have an expedition then,” David said. They disappeared down the hall.

“Wow,” Theresa said. “I should have brought Luisa here earlier. She’s actually playing well with others, sort of.”

“My son was angry,” Ernesto said in English. “He left home when he was fourteen.”

“What happened to him?”

“No say. No say.”

“Uplifting story, Ernesto,” Theresa said.

He shrugged.

A few minutes later, David returned with the children. Luisa carried a cardboard box. She set it on the table and took off the lid.

“Mom must have saved this stuff,” David said. “I haven’t done art in years.”

“I thought you got a degree in art education,” Myla said.

“Didn’t pan out,” he said.

“Look,” Luisa said. “We’ve got colored pencils and pens. And glitter glue. Sequins. Beads. We can make these mermaids into babes.”

“Some of these babes are going to have mustaches,” Stefan said, holding up a Jack.

“Some of the best women I know have mustaches,” Myla said.

Cathy and Theresa made coffee while everyone else sat around the table with the face cards. Luisa began coloring on a queen. Stefan took a jack. Lily a king.

Lily asked her mother what she was supposed to do.

“We’re making them into Old Mermaids,” Maria said in Spanish.

“You too, Maria,” Myla said. “David. You haven’t done art in years? Now is the time. Your life is your art statement. Everything is about art!”

Soon, the table sparkled with glitter. Sticky glitter. Luisa used sequins to approximate the scales on the Old Mermaid’s somewhat truncated tail. Lily glued sequins everywhere and then added glitter. Maria shredded ribbon David found in his mother’s sewing basket and made it into hair for her mermaid. Ernesto drew in a hammer and nails. “Someone has to do the work around the sanctuary,” he said. David’s mermaid seemed to get darker and darker the longer he worked on the card. Stefan colored in the mermaid and then added more figures so it looked like a tiny mural.

“I wish these cards were bigger!” Luisa said.

Myla walked around the table and looked at the artwork.

“That one with the green tail, Luisa,” Myla said. “She reminds me of Mother Star Stupendous Mermaid. She was very wise. You have a wisdom about you, too. That must be why you thought of her. She listened and thought about things a great deal.”

“She was wise and beautiful,” Luisa said.

“Of course,” Myla said. “And yours, Lily. Ahhh, I think that might be Sister Laughs A Lot Mermaid. She is a happy glittery kind of Old Mermaid. Now Stefan, that must be Sister Magdelene Mermaid. They call her Sissy Maggie. She’s very artistic. You’d like her. Maria, which Old Mermaid is that? I think it might be Sister Bridget Mermaid. She had long curly hair, a bit red. I know what you’re thinking. All Old Mermaids have long hair, but that isn’t actually so. Some do have long hair; some don’t. Sister Bridget Mermaid knows all about poetry, herbs, plants, songs, healing. She and Sister Faye Mermaid plan the parties and ceremonies for the Old Mermaids. They know when the moon is full or when it is dark. They know the best sea chanties. Ernesto, that has to be Sister Sheila Na Giggles Mermaid. She is practical, too, and very handy around the house. She tells it like it is. If she thinks someone is getting too fanciful, she’ll say, ‘Get the starfish out of your eyes, Sister Mermaid.’ And she knows the more colorful sea chanties.” She walked over to David. “Ahhh, this must be the Grand Mother Yemaya Mermaid. She knows more about the oceans and seas than anyone. She knows more about the mystery of ourselves—our watery bodies—than anyone. She is like your grandmother, Maria. She has moon beauty. When you feel as though you are drowning, she is the Old Mermaid who will save you.”

“That’s only six,” Luisa said. “We’ve got seven more to do.”

“Next week,” Theresa said. “It’s getting late. Some of us have had a long day.”

Luisa looked disappointed. “We still haven’t played Old Mermaids.”

“David, can we leave this stuff somewhere here?” Myla asked. “Then they could finish it next Saturday.”

“I don’t know if I’ll be here, but I’m sure my parents wouldn’t mind.”

“I’ll take everyone home,” Theresa said.

Myla glanced at Luisa who was putting the supplies back into the box.

“Oh, wait,” Theresa said, understanding Myla’s hint. “Um, I forgot. I’m not going that way.”

“What way?” Luisa asked. “We can take them. Come on, Mom.”

She was sharp as a tack, this one.

“I need the exercise,” Ernesto said, “so I’ll walk.”

“Yeah, us too,” Stefan said.

Luisa shrugged. “Whatever. See you later, gators.” Her mother handed her the empty bowls.

“Sorry to leave you with this mess,” Theresa said to David. “My husband and I are newlyweds, sort of. He misses me, so I better get home.”

Luisa rolled her eyes. “Yeah, good old Del Rey. We should have had him here tonight. Hearing you all talk about communes would have given him a heart attack. He’d probably think you were communists or something.”

“He’s not like that,” Theresa said. “Don’t pay any attention to her. He’ll come sometime, I promise. Night!”

Theresa and Luisa left.

“Can I say good night to the mermaid in the pool?” Lily asked.

“I’ll take you out,” Myla said. “We don’t want you to go out to see the Old Mermaid in the pool without one of us going with you.”

“Why?”

“Because the water is deep,” Maria said.

“The Old Mermaids said they would teach me to swim,” Lily said.

“Oh really?” Maria asked.

“The Old Mermaids come to me in my dreams. And they’re teaching me.”

“Well, we’d feel better if you only went out to the pool to see the mermaid with one of us,” Myla said. “And don’t ever try to swim without one of us there, even if the Old Mermaids have taught you to swim.”

Lily nodded. “Okay.”

The girl took Myla’s hand, and they walked through the living room out to the patio. The pool light was the only illumination. The two of them walked to the edge of the pool and looked down at the mermaid. After a few moments, Lily began nodding, as if she were listening to someone speak.

Myla sat near the edge of the pool. Lily sat next to her.

“What are you listening to?” Myla asked.

“The Old Mermaids,” she said.

“Oh? What are they saying?” Myla asked.

“Not to be afraid,” Lily said. “They sing to me while I sleep.”

“What kind of song?”

“A not-be-afraid song,” Lily said.

“That’s good,” Myla said. “Then you probably don’t need what they left in the wash for you.”

“What is it?” Lily asked.

Myla carefully took the dreamcatcher earring from her pocket. She handed it to Lily.

“This is called a dreamcatcher, Lily my Lily,” Myla said. “If you put it in your room, it’ll take away all the bad dreams. A Native American healer gave one like it to the Old Mermaids when they first came to the sanctuary. It was all new to them, and some of them were afraid. Sister Laughs A Lot Mermaid, who was the youngest, had bad dreams. When the medicine man gave her this dreamcatcher, the bad dreams went away.”

Lily nodded solemnly.

“Sometimes when I open my eyes in the dark, I see it all moving,” Lily whispered.

“What’s moving?” Myla asked.

Lily whispered, “Everything. Like when we crossed the river. The water pulled on me. And there were flashes of light in it. I couldn’t keep a hold of Momma’s hand.”

“That must have been very scary,” Myla said. “Have I told you much about Grand Mother Yemaya Mermaid?”

“A little.”

“Well, she is the wisest of wise,” Myla said. “She is one of the ones who is a moon beauty, like your great grandmother. And her skin is as dark as night. Darker. She is so grand that she had two tails before the Old Sea dried up.”

“The Old Mermaids don’t have tails any more?” Lily asked.

“Well, that’s a good question,” Myla said. “They do and they don’t. If you were to see them most days, you would not see a tail. You would see only their legs. But other times, if the light is just right or if you are a bit sleepy, you might be able to see the glitter of their tales—as though they are wearing beautiful gowns—with flashes of color and light. In a good way, not like your scary flashes. And if you wake up and the darkness frightens you, remember Grand Mother Yemaya Mermaid is there with you. She is the darkness that protects you. Those flashes of color and light are just her mermaid tails.”

Maria came to the patio door. “It is time for bed, Lily.”

Lily waved to the mermaid in the pool. “Buenos noches!” Then she threw her arms around Myla’s neck and hugged her. “Good night, Myla Mermaid.”

“Good night, sweetheart.”

The girl let go and ran to her mother.

“Good bye, Myla!” she heard the others call. Myla waved, then looked down at the mermaid in the pool. She was suddenly very tired. She wasn’t sure she was up for her yearly sojourn with George tomorrow.

The patio door opened and closed. Myla looked up at David. He sat next to her. She put her hand on his back.

“I’m sorry I sprung all this on you,” she said. “You wanted to rest and I gave you us.”

He smile and took her hand in his.

“Oh!” Myla said. “I felt a spark.”

“Sorry about that,” David said.

“It’s very dry in the desert,” Myla said. They were silent for a moment. She laughed. “I suppose that’s like saying the ocean is wet!”

David laughed. “You always knew how to draw me back into things,” he said, “especially when I didn’t want to be drawn in.”

“That’s an interesting choice of words, David. ‘Drawn’ into things. You gave up your art? Your mother didn’t tell me.”

“So many school districts have cut out all the art programs,” he said. “And I didn’t want to teach anything else. So I got my MBA, and I’ve been brokering deals between small struggling companies and larger corporations so that the small companies can keep doing what they’ve been doing using the backing and capital of a big company.”

“Sounds like it could be interesting,” Myla said.

“Except most of the time it didn’t work,” David said. “At least not the way I envisioned it. If it was a small company doing business sustainably, the corporation would always put pressure on them to be more profitable. Even if they were profitable, the corporation wanted more profits. I kept wondering when is more enough?”

“So you’ve taken a break from all that?” Myla said.

“I quit,” he said. He rubbed his face. “I’m done with it.”

“You look tired,” Myla said. “I’ll clean up. You go to bed.”

“You’re just about perfect, aren’t you, Myla?”

“Don’t you say that,” Myla said. “You knew me way back when. You know I’m not perfect—whatever that means.”

“You were always kind,” David said. “And beautiful.”

Myla laughed. “I was ragged from a bad divorce. I can’t imagine I was nice.”

“I didn’t say you were nice,” David said. “You always told me nice is overrated, but kindness is a gift. Kindness is acknowledging that we are all kin. Nice is a fake smile, trying to cover up the truth, which is often dark and painful.”

“I said all that?” Myla said. “I don’t remember. I don’t remember a lot about that time.”

“Do you remember all the time we spent together?”

Myla said. “I remember you painted this mermaid and everyone thought it was me. I remember we walked the wash together.”

“Do you remember we talked about starting a school together?”

“Together?” Myla said. “Did we? Yes, now that you say that. What else? Have I forgotten anything important?”

“No, no,” David said. “That was it. I think I’ll go in now. You don’t need to clean up. I’ll do it in the morning. It’ll give me something to do.” He stood and reached a hand down to Myla. She took it and let him pull her up.

“If you say so,” Myla said. “I’ll see you in the morning.”

“Good night, Myla Mermaid.”

George knocked on Myla’s door too early the next morning. When she didn’t answer it, he opened it and came in to the apartment. Myla covered her head with a pillow. George whistled.

“Come on, girl,” George said. “The day is wasting. I brought bagels, croissants, coffee, and orange juice.”

Myla sat up and pushed her hair out of her eyes.

“You really have got to stop this boozing, Myla,” George said. “The hangovers are awful.”

“Very funny,” Myla said. “Any protein in that bag?”

George sat on the bed and opened the white sack. He reached in and pulled out two boiled eggs. He tossed one to her. She tapped it against the wall until it cracked and then began pulling the broken shell off of it.

“George,” Myla said just before she bit into the egg.

“Yes, dear?”

“Do you ever think perhaps we’re getting a bit too old for this? It has been ten years.”

“Maybe,” he said. “But I’m here. We might as well go.”

Myla got out of bed and took off her red cotton pajamas. She didn’t care that George watched while he ate a bagel and gulped coffee. He watched her like she imagined he watched a football game or an animal crossing the road in front of him: with interest but without enthusiasm.

“I like your curves, woman,” he said.

Well, maybe she was wrong about the enthusiasm.

“Thank you, George.”

She pulled on a pair of slacks and tucked her camisole inside them. Then she took a purple shirt from her small closet and put it on.

“He got that right,” George said.

“Who got what right?”

“The guy who painted the mermaid in the pool got your curves right.”

“What made you think of David Crow?” Myla asked.

“I saw him as I was driving up.”

“You recognized him?”

“He looks the same to me. I remember him because he tagged along with you a lot then. You even let him walk the wash with you. You never let me do that.”

“That’s because you talk too much.”

“He had quite a crush on you,” George said. “Made me a little jealous.”

“David? I think you’re mistaken. I’m almost as old as his mother. Well, not quite.”

George shrugged. “I’m telling you. Men know about this kind of stuff.”

“Oh really?”

“About other men. Sure.”

Myla snatched the paper bag from him. “George, you’re talking nonsense. Let’s go.”

They drove to their old neighborhood. Brick houses predominated, making it look like a suburb in the Midwest. Or someplace like that. Myla had never actually been to the Midwest. She only knew these houses did not look like desert houses. She wondered why she had ever agreed to live here. Had she actually liked it? George slowed the car as he turned the corner onto their old street. He parked two houses away from his old house, three from her old house. Her ex-husband’s car was in the drive. At least that was the car he had last year. Several plastic children’s toys were strewn around the yard. They had finally taken out the grassy lawn and replaced it with rock. About time.

George relaxed against his seat and lifted a cup of coffee from the paper sack.

“I heard the shop isn’t doing well,” George said. “I bet you’re glad you took a lump sum.”

Myla didn’t say anything. She stared at the house. Would her ex look different this year?

The front door opened and George’s ex-wife, Nadine, stepped outside. A nine-year-old girl came out next. Or was she ten now? She had been born a few months after Myla and her husband broke up—a few months after Myla found her husband on top of Nadine, in Myla’s bed. Nadine had been naked, her breasts heavy—when normally they were small—and her belly round. Myla knew then why this thin young woman had been wearing baggy clothes for months. Still, it had taken her a moment to grasp what she and George had walked into, so she said, “Congratulations. You look just like those pictures of the pregnant Madonna.”

“Only the Madonna isn’t naked,” George had said. Something about George’s voice had woken her up then. She had blinked and realized her naked husband was getting dressed, and Nadine was crying.

“It can’t be mine,” George had said. “She hasn’t let me come near her for a year or more.”

Now Myla felt a tickle in her stomach.

“George, I think we should go home.”

“Wait,” he said. “Just a bit longer.”

Then Richard—Myla’s ex—stepped outside onto the steps and shut the door behind him. Nadine looked back at him and smiled. Myla could see his lips moving. He looked old enough to be Nadine’s father. She was what now? Thirty-five? And he was fifty-five. Myla had been twenty-three when she and Richard married; he had been over thirty. Both old enough to know what they were doing.

The family got into the car. The girl laughed. Or whined. Myla couldn’t be sure.

“The girl looks just like her,” George said. “That could have been my kid.”

“I thought you didn’t want children,” Myla said.

“That’s beside the point.”

The car backed out of the driveway. Then they drove by Myla and George. George stared right at Richard, but he was talking and looking ahead.

“God I hate him,” George said.

Myla said, “I don’t hate him. Or her. That can’t be good for you to hate them.” She sighed. “George, I’m going into the house.”

“No, you’re not,” he said.

She put her hand on the door handle. “I am. I want to see it. It was my house. The only house I ever owned. I feel as though I was evicted and never got a chance to say goodbye.” She didn’t know if any of what she said was true. Maybe she had said goodbye. She could not remember any quiet contemplative moments from that time, but that did not mean she hadn’t had any. What she did remember was that it had been her home and then suddenly it wasn’t. After she saw Richard and Nadine in bed together, the house had felt contaminated, and she had to leave it.

“If you go in,” George said, “I’m driving away.”

“Oh you are not,” she said. “I’ll be right back.”

Myla got out of the car. She crossed the street, went up the driveway, and through the paved path between the carport and the house around to the back door. She stopped for a moment and breathed deeply. Then she went up the steps and opened the screen door. Then she put her hand on the back door knob, turned it, and pushed the door open. She stepped into cool semidarkness and quietly closed the door. The house pulsed with silence. On her tiptoes, Myla walked across the kitchen to the living room. Different furniture and arrangement. Same coffee table. The house looked familiar but different. Smaller. Stuffier.

She walked down the hallway. Four doors. Two closed. Two open. The first closed door was the bathroom. She carefully opened the door and looked inside. She didn’t recognize anything. It had been redone in red and white. She shuddered and closed the door again. The second closed door was what she and Richard had used as a guest bedroom. She opened it. Now it was a little girl’s room. Pale blue and white. A small canopy bed. A little dressing table. Someone had painted pastel-colored stars on one wall. It was a beautiful room—cluttered and messy—just like a young girl’s room should be. She closed the door again.

Now she was at the end of the hallway. The master bedroom. The door was wide open. There was the bed. It looked like the same bed. Same headboard. Was that possible? Richard was extremely frugal. Cheap, actually. He never replaced anything until it broke. Nadine had probably wanted to get rid of the bed he had shared with Myla for fifteen years, but he wouldn’t do it, Myla guessed. She stepped into the room. Their old dresser was still here. She had found it at a garage sale. Beautiful old oak dresser. Richard hadn’t wanted it. She insisted—one of the few times in her marriage that she had insisted. Ordinarily when they disagreed about something, she usually gave up—worn down by their “discussions” which usually consisted of him haranguing her until she came around to his viewpoint, or at least she pretended she did so she get him to shut up. When she married him, she had thought he was a great debater, a man with an intellect. She shook her head. Had she really ever been that naive? She ran her hand over the top of the dresser. She should have taken this with her. She had not taken much—only her clothes, gardening tools, books, and a few pots, pans, dishes.

She walked to the bed, put her hand on it, then sat on it. She bounced on it, slightly. Then she lay back and looked at the ceiling. It was comfortable. They must have gotten a new mattress. She closed her eyes.

A toilet flushed.

She sat up.

Someone was in the master bathroom. Right behind her.

She jumped up and ran out of the room.

“Is someone there?” A woman’s voice.

Myla ran through the living room and into the kitchen. Then she stopped. She couldn’t help it. She stared at the tiled kitchen wall. Her tiled kitchen wall. When she and Richard had first moved into the house, they had decided to put in a tile backsplash. She had wanted to tile the whole wall beneath the cupboards and above the sink, but she hadn’t been able to convince Richard. He thought it would be too expensive.

One day he took her into the back room of the shop.

“I have a surprise for you,” he said. He opened up a box of tiles. Myla began pulling them out. Some were indigo blue, others were light green, and others had seashore scenes painted on them: sea shells in the sand, clams, starfish in the ocean, sea gulls against a blue sky.

“These will be big sellers,” Myla told him.

“No, they’re for our kitchen.”

“But these are ocean scenes,” she said. “They’re better suited to the bathroom. Or somewhere near an ocean. I want desert scenes. We live in a desert.”

“This whole desert was once an ocean,” he said. “And you can do the entire wall beneath the cabinets if you use these. I got a good deal on them.”

Myla had finally agreed. She and Richard had tiled the wall themselves.

Now Myla walked closer to the wall, her hand outstretched. She walked until her fingers touched one tile over the sink, at the center, right above the faucet: a tile of a mermaid.

How could she have forgotten this? She had looked at this mermaid every day for years. This mermaid had made the ocean tiles work for her. She had loved seeing the mermaid every time she came into the kitchen, every time she did the dishes. Until—

Until she forgot to look?

“Who are you?”

Myla turned around. An older woman stood in the kitchen behind her, holding a phone.

“I’m going to call the police,” she said.

Myla said in Spanish, “No habla English. I’m the housekeeper.”

“On a Sunday?”

“Est Sunday? Oh! I’ve missed mass then! Lo siento, lo siento!” Myla hurried out the back door. She ran around the house and across the street to George’s car.

“Hurry!” she said as she got inside. “We’ve got to get away.”

“Why? Did you steal something?” He started the car.

“No. Someone was there!”

George quickly drove them out of the neighborhood and onto a main street.

“Who was it?” George asked.

“I don’t know!” Myla said. “Some older woman. Maybe Nadine’s mother.”

George laughed. “I hope so.”

“Why?”

“Because her mother hated him,” George said. “Believe it or not, she liked me. And she was very upset when we got divorced. She could be really mean. I hope she’s living with them!” He laughed loudly. “Out into the desert for our celebration?”

“No,” Myla said. “I don’t feel like it.”

“Home then for some midday delight?”

“George, take a hint.”

“Sorry,” he said. “What was the house like?”

“It wasn’t much different,” Myla said. “He’s still a cheap s.o.b. They’re using some of our old furniture. Even our old bed.”

“That’s kind of creepy,” George said.

“And us going over there once a year and me sneaking into their house is normal?”

“Did it still feel like your house?”

“I’m not sure,” she said. “But I started remembering some things.”

“Like seeing them naked together, his—”

“George.”

“Okay. Like what?”

“Like the kitchen tile. There was a mermaid.”

“Huh,” George said. “I don’t remember that.”

“Why would you?” she said. “It wasn’t your house.”

“So what if there was a mermaid?” he said.

“Take me home, George.”

She closed her eyes and leaned her head against the window. She had had a mermaid in her previous life. How could she have forgotten that? For the last decade she had been certain that the Old Mermaids were only part of her new life—conjured to save her, to help her reclaim her life and find purpose. The Old Mermaids had absolutely nothing to do with her old life.

When she first started the Church of the Old Mermaids—after the dream—she saved the money she earned. It wasn’t much, but she knew she would figure out what to do with it eventually. One day during a trip out into the desert searching for treasure, she saw a group of people in the sandy bottom of an old wash. She went over to say hello. Three men, a boy, and a woman sat on the dirt, too exhausted to move. Myla immediately offered them water. They gave it to the barely-conscious woman first. Myla wanted to take them to the hospital, but they refused.

Once they drank the water and ate the food she gave them, they revived. They had crossed the border illegally, as she guessed, and had been deserted by their smuggler—the guia—soon after they crossed. Myla took them to her apartment in the Crow barn, fed them, and let them use her phone. The woman—Grace—was too ill to leave with the others, so Myla let her and her son, Roberto, stay. She didn’t even think about it. She got her keys and drove them over to the Ford place and let them sleep there. The Old Mermaid Sanctuary—in its present form—was born.

Two days later, using some of the money she had earned from the Church of the Old Mermaids, Myla bought Grace and Roberto bus tickets to Texas where Grace’s husband worked in the fields. After taking them to the bus station, Myla came home and went to the Ford house to clean it, but the house was spotless, the garden tidy, the dirt raked. Myla believed the house felt better too. Which was how it should be, she decided. A house was created to be lived in. That was its purpose. When the Fords returned, they even remarked that the place had never looked better.

Myla kept making excursions to the desert, near la frontera. Sometimes she found people, sometimes she did not. She was careful about who she brought home with her and even more careful about who she let stay in the houses. When she told Theresa what she was doing, Theresa offered to help. Myla was glad to have her as a partner, especially since Theresa was a private investigator and many of the migrants came looking for family, friends—and a job. After a while, Theresa and Myla began going to the desert together, mostly in the summer when it was so dangerous for those crossing. In recent years, they sometimes encountered people from Humane Border, who left water in the desert for the migrants, or the No More Deaths volunteers who sometimes transported migrants to the hospital, all activities which had been deemed legal until recently. A few months earlier a couple was arrested as they drove several people to an area hospital. They were charged with aiding and abetting illegal aliens. Or something like that. Myla knew if she got caught, she wouldn’t be able to help anyone, so she and Theresa kept quiet about what actually went on at the Old Mermaid Sanctuary, and they avoided the other rescuers as much as possible.

In the winter, the Sanctuary was usually quiet, except for visits from the homeowners. Summer was busier. Myla made certain each house was not occupied often or for very long, and visitors always did work around the property in exchange for their room and board. One year a family retiled the Castillo roof. Another time, a man helped fix the greywater irrigation system at the Ford house. Myla told the migrants that if anyone happened to see them and ask what they were doing there, they were to say that Myla had hired them. After all, the homeowners had instructed her to keep up the yards, facilitate repairs, and make the houses looked lived in. Myla made certain all that happened—only the workers stayed in the houses while they did the work.

Myla kept an Old Mermaid Sanctuary binder. In it, she put photos of the visitors with their names, ages, which house they stayed in and what work they did. Almost always, the migrants sent Myla a postcard once they were settled, and she’d add those to the binder.

Myla understood that these niceties would not placate the owners should they ever learn of her venture. She knew they would view what she was doing as a betrayal. Criminal even. She knew she could not adequately explain what she was doing and why; she could not tell them that the Old Mermaids had come to her in a dream and that she was doing their work here on dry land. That would sound crazy. Or—at the very least—possessed. She had tried to figure out other ways to explain what she had done—what she was doing. It wasn’t like she thought God had spoken to her, or that she was channeling Ramtha or that she’d seen a vision of the Virgin Mary. It was more like the Invisibles of the land—and the sea—had spoken to her. But that wasn’t right either. The land and its occupants were always speaking—and she just happened to be able to understand them one morning a decade ago, and now she always heard them, in the form of the stories that poured from her mouth like a wonderful kind of babel—or babble—which most people, fortunately, understood. (She had encountered the occasional visitor to the Church of the Old Mermaids who said something like, “I see your lips moving, but all I hear is nonsense.”)

Now after seeing the mermaid tile in her old house, Myla wondered about her raisin d’etre. Maybe the Old Mermaid dream had only been a bit of undigested memory making itself a character in her vision. Maybe she had concocted the Old Mermaids as a way of hanging onto some shred of her former life.

George stopped the car. Myla looked up. They were home.

“You sure I can’t come in?” George said. “It’s tradition.”

“Maybe sometime we can go on a real date,” Myla said.

“A date? Now that’s crazy talk.”

Myla leaned over, and they kissed.

“See you later,” Myla said.

“I could come in, and we could just talk,” George said. “You seem a little lost.”

“Thanks,” Myla said. “You’re welcome to come to Saturday dinner though. You always are.”

Myla got out of the car and then shut the door. As George drove away, she stood in the drive listening to the silence for a few minutes. Then she went to the edge of the wash, stepped down onto the sand, and walked unsteadily until she came to a wide stretch. She looked north, and she looked south. The wash disappeared into desert trees. She looked east, and she looked west.

What if it had all been a dream? No call to action. No cosmic message. Only a dream.

She heard crunching in the wash and turned in the direction of the house. A moment later Gail came around the palo verde bend; Theresa followed.

“I figured you’d be here,” Gail said.

“David said he’d seen you go this way,” Theresa said.

“You two together?” Myla asked.

“No!” they said at the same time.

“Thought you might need company,” Gail said. “How about that movie?”

Myla turned around again and kept walking.

“I don’t feel like a movie,” she said.

“I’m glad to see you decided not to go to your old house,” Gail said, following her. “Don’t you get a lot of sand in your shoes when you do this?”

“Decided not to go where?” Theresa asked. “You need to wear walking shoes, Gail. Or something to protect your feet. You’re in the desert, for chrissakes. A scorpion or rattlesnake would bite right through those tiny little things.”

“I did go to the house,” Myla said.

“What house?” Theresa asked.

“Her old house,” Gail said. “It’s the anniversary of her catching her husband doing the nasty with her next door neighbor.”

“Why on Earth would you go back there?” Theresa asked.

“Well, it used to be her house, too,” Gail said. “I remember when she moved in there. Kind of a strange little house. Looked like it didn’t really belong here—you know—in the desert.”

“Do you remember we redid the kitchen soon after we moved in?” Myla asked. She stopped and turned to her friends.

“Vaguely,” Gail said. “You used some strange tiles. Bathroom tiles or something.”

“You remember that?” Myla asked.

“Probably just because I thought it looked stupid,” Gail said.

“I was never at your house,” Theresa said. “I met you right after you came here.”

“Do you remember there was a mermaid tile?” Myla asked.

“A mermaid tile?” Gail said. “In the kitchen? No, why?”

Myla shook her head. “I had a dream, remember? The Old Mermaids came to me in a dream. I thought it was a message from the Universe. I thought they were telling me what I should do with my life.”

“Why would you want anyone to tell you what to do with your life?” Theresa asked.

Myla made a noise and continued walking. “I don’t mean like that. It was like a sign that I could go on, that I could make a difference. I mattered. I can’t explain it!”

“I think I know what you mean,” Gail said.

Theresa frowned. “A message from God? I don’t believe in God.”

“Theresa, we’re talking about me,” Myla said. “I didn’t say anything about God. I said Universe. The Old Mermaids were about my new life. They had absolutely nothing to do with my old life.”

“And because there was a mermaid tile at your old house, you’re doubting your mission, or whatever it is?” Theresa asked. “Come on. There are mermaids everywhere. They’re a ubiquitous symbol. You didn’t make up mermaids.”

“She did make up the Old Mermaids,” Gail said. “They’re pretty cool.” Myla looked at Gail. Gail shrugged. “You don’t think I pay attention, but I do. The Old Mermaids are interesting.”

“I didn’t make them up,” Myla said. She did not like talking about the Old Mermaids like this. It seemed rather sacrilegious—gossipy. “I don’t want to talk about it.”

“You always want to talk about everything,” Gail said.

“No, not the Old Mermaids,” Theresa said.

“What are you talking about? She is always talking about the Old Mermaids. She spends every Saturday talking about them nonstop.”

“That’s not talking about them,” Theresa said. “That’s more like being with them. It’s like remembering interesting stories about your family and then sharing them.”

“Exactly,” Myla said. Although not quite. She stopped abruptly and looked down. “This is why I don’t let anyone walk the wash with me. If you’re talking all the time, you don’t see what’s right in front of you.”

Gail and Theresa came up beside her. Directly in front of them was a shoe in the sand.

“Looks like a dog gnawed it all to bits,” Gail said.

“More likely a coyote,” Theresa said. “Hardly anything left but the sole. Wow, Myla. You really do find things here. That’s perfect. What a story you could make out of that. Someone must need a soul.”

“No, I think it means someone should bare their soul,” Gail said. “See, because it’s been eaten down to the sole.”

“It’s more like someone lost their soul,” Theresa said.

“Someone lost their shoe,” Myla said. “And now it’s a coyote plaything.”

“You mean you aren’t going to take it?” Theresa said.

“No,” Myla said. She stepped over it and kept walking.

“I think it’s a message for you,” Gail said. “The Old Mermaids want you to bare your soul. To us. You can talk to us, Myla. We’ll listen.”

Myla groaned and turned around. Ordinarily, she was a patient and good-natured woman. Beyond her friends she could see the log wrapped in orange rope. Maybe it was time she unraveled that rope because she suddenly felt at the end of hers. Just then, David came into view. He stepped over the log. Luisa scrambled behind him.

“Hello,” David said.

“I know you,” Gail said. “You’re David Crow.”

“You remember him after all these years?” Myla asked.

“You were just talking about him yesterday,” Gail said.

“She was talking about me?” David asked.

“You’re the one who painted the mermaid in the pool,” Gail said.

“You painted that mermaid?” Luisa asked.

“Myla said that last night,” Theresa said.

“Well, I didn’t hear her,” Luisa said. “That mermaid is naked and everything. And she looks like Myla. Not that I’ve ever seen her naked.”

“The mermaid is not naked,” Myla said. “She has a tail. David is an artist. He extrapolated.”

“Technically, she is naked,” Theresa said. “A tail doesn’t constitute clothing.”

“In any case,” Myla said.

“What does extrapolate mean?” Luisa asked.

“I’m not sure,” Gail said. “Could you use it in a sentence?”

“I just used it in a sentence!” Myla said.

“Could you use it in another one?” Gail smiled. Myla started to laugh. Soon the three women were giggling. Luisa and David watched.

“What?” Luisa asked.

“Nothing,” Theresa said. “You had to be there.”

“I was there,” Luisa said. “Here. Whatever. Are we going to a movie? Or would you like to paint another mermaid, David? I could be your model this time.”

“I was not his model,” Myla said. “Would you all please go away? I don’t want to go to a movie. You go. Theresa and Gail, you need to get to know each other better. Learn to like one another. Get along together. Show Luisa how it’s done. Luisa, you are not going to pose naked for this man or any other man. Or woman. Not today. Away!”

“All right,” Gail said. She embraced Myla.

“Okay, okay, let her go,” Theresa said. She hugged Myla. “I love you.”

“I love you too,” Gail said.

“Go away,” Myla said. “Well, except David. You live here. You can stay.”

The two women and girl walked away together. Myla stood still until she no longer heard their voices.

David looked down at the shoe.

“A sole,” David said. “I wondered where I had lost that. Just what I needed.” He picked it up. “See you later, Myla Mermaid.” Then he turned and left Myla alone.

That was just what she needed.

7.07.2008

COTOM: Chapter Four

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Kim, I've always loved Myla and COATOM, in fact I am reading it again! Love, Cate

Post a Comment