I was baffled but interested when these mermaids appeared in my imagination, so I started doing research on mermaids. I learned that one of the first depictions of a goddess was the Syrian fish-goddess Atargatis (who was also known later as Aphrodite). In fact, many cultures had stories of ancient fish-tailed goddesses and myths and legends of mermaid-like creatures belonging to seas, oceans, and lakes. It seemed the modern mermaid was a transformation of the ancient goddess from a powerful creatrix of all life to a kind of fish-tailed Barbie.

During this time, I saw a painting of Yemaya rising out of the ocean—her skin black and her tail bright blue—and I was filled with awe. I could almost hear her head breaking the surface of the water as she rose, could almost feel the drops of ocean and sense the sea shiver as she made Herself visible. I understood then, fully, the power of the symbol of woman as part fish. She was the ocean and she was woman. She was all powerful—the birthplace of life.

Mermaids are ubiquitous these days. Young adult novels are swimming with mermaids. Depictions of them are all over the internet. Is this commercialization of mermaids watering down their power? Or have their powers already diminished over time? After all, most of us have either forgotten or never knew their genesis as fish-tailed goddesses of birth and death.

My 7-year-old neighbor likes mermaids. The other day she brought over one of her favorite books about a Barbie mermaid, along with several small Barbie-like mermaid dolls. They looked alike, all very thin with bigger breasts than a real woman that thin would actually have. Nothing powerful or goddess-like about these creatures. They struck me as the latest doll form of woman as a kind of monoculture.

Despite the Barbie-ization of mermaids, I wondered why these particular mythological creatures had suddenly become so popular. It could just be the whim of culture or some form of commercialization?

Then why did they show up to me eight winters ago, before this present mermaid craze? They came into my imagination and I wrote about them. And I keep writing about them. I’ve never written about the same characters or the same world before. Since

Church of the Old Mermaids, I wrote a kind of prequel to it,

The Fish Wife. And the Old Mermaids are supporting characters in

The Desert Siren and

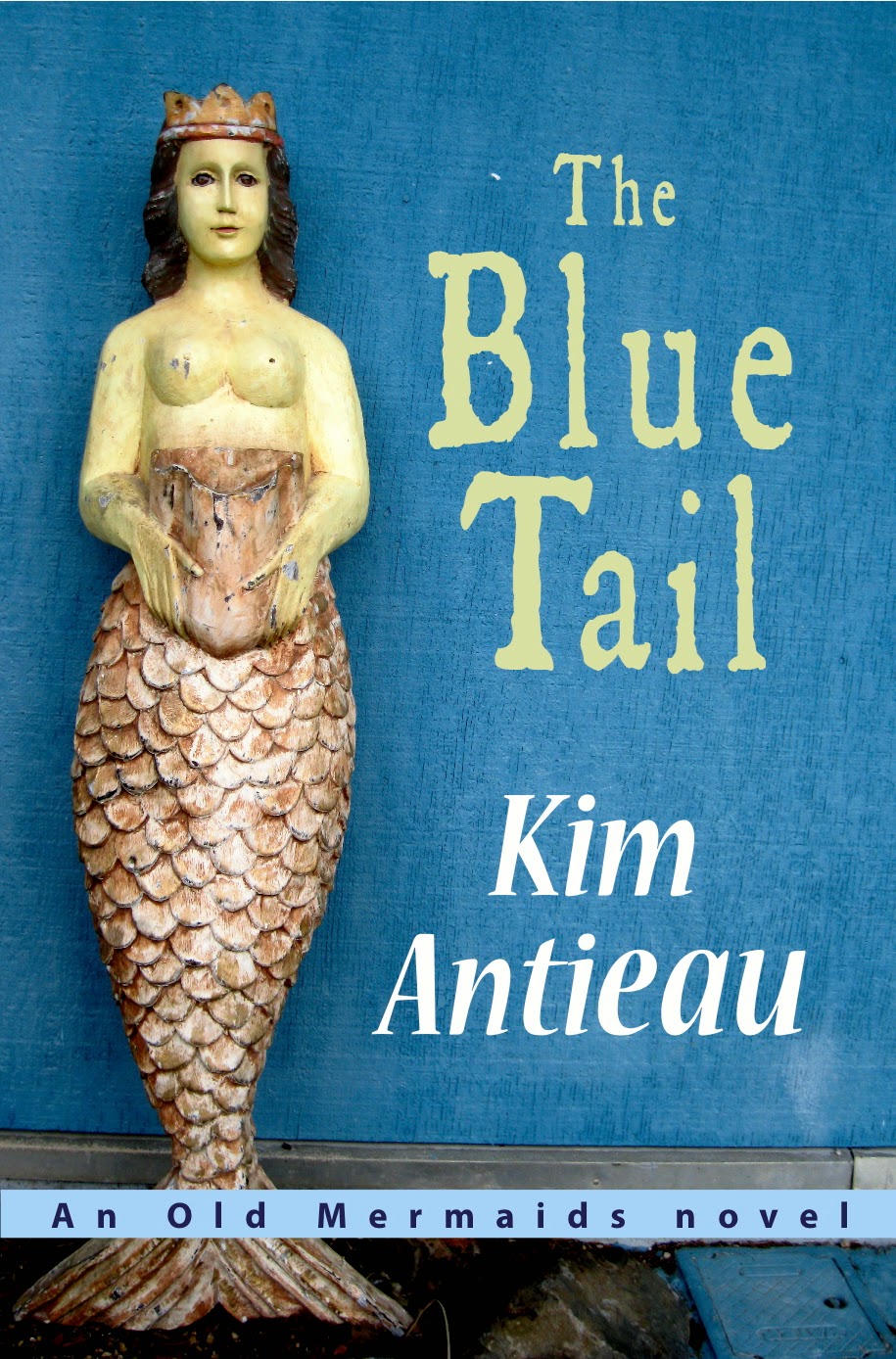

The Blue Tail. I’ve put together a book of quotes (mostly culled from the Old Mermaids books) called

The Old Mermaids Book of Days and Night. And I have many other Old Mermaids novel in mind.

Why now? Mermaids come from the watery realms. Carl Jung and others might say they represent the feminine—maybe even the submerged feminine. Perhaps it’s more literal than that. Could it be they’ve stepped out of the Imaginal Realms to remind us that we are the blue planet, the water planet, and our waterways are in trouble? Without clean oceans and rivers, we die, along with most other creatures on this planet. As climate change wreaks havoc on our weather systems and drives water temperatures dangerously high, is it any wonder that a creature from the watery depths rises up and cries, “Answer the call to the wild! It is time. Wake up, now. Wake up!”

Where I live in the Pacific Northwest, Sasquatch is part of the local legends. You don’t have to go far before you find someone who has a story about seeing or almost seeing Bigfoot. But according to some Native American beliefs, Sasquatch only shows up when life is out of balance: You do not want to see a Bigfoot because it means things are either going bad or about to go bad.

Maybe mermaids—in my case, Old Mermaids—are appearing to warn us or to show us that life is out of balance.

I know that sounds like a stretch. One could ask, why are vampires so popular then? What message from the collective psyche do they bring? I really don’t know. But I do believe stories are important. I believe storytellers are voices for the planet: We speak for the planet and all her creatuares. Some stories—maybe all?—come to us from the Imaginal Realms for some reason: to teach, enlighten, warn, encourage.

When I was 19 years old, I tried to kill myself. I didn’t want to die, but I wanted the awful emotional pain to stop. Afterward, I moved out of the house I shared with three other women and into a tiny attic apartment. For weeks (maybe even a year), I barely said a word to anyone—beyond what was necessary to get through the day since I was working and going to school full time. One night I dreamed about a watery nymph. I remember thinking she was a naiad even though I didn’t actually know what a naiad was. She had water and seaweed running up and down her very white body. She had big soulful eyes. In the dream, we made love all night long. It was a profound healing. When I awoke the next morning, I began to recover and I knew I would survive. Years later, I realized she was probably my first encounter with the Old Mermaids.

Mermaids next appeared to me eight winters ago, just two months before I had two surgeries (when I wrote Church of the Old Mermaids), and they haven’t left me since. I’ve felt like their appearance in my life has been tantamount to a miracle.

Can they be more than that? Are their appearances or re-appearances on this planet a siren call to us all? Can the stories about them be more than escapist fiction? Can the mermaids—and Old Mermaids in particular—help us uncover or compose our own siren songs—that part of us that is true and valiant and able.

I hope so. I hope we can finally and forever be full of our powerful true wild oceanic selves—we can be sea women and men—ready to ride the waves of our lives and fix that which is broken and heal that which is sick.

After all, we are creators and destroyers, poets and dreamers, artists and musicians, cooks and gardeners, mystics and conjurers, leaders and mediators, witches and sorcerers. It is time to awaken and heal ourselves and the world.

(Artwork in public domain, from 1880s poster of a snake charmer; used now as common depiction of Mami Wata, water goddess of the African diaspora.)